Campbell Arnott’s, a company with a deep cupboard of iconic Australian brands, was sending out a good vibe, or chime, at the very first pitch session -- the brief.

The Publicis Groupe team felt the, hopefully, client-to-be was clear about the objectives and had an open mind on how to get there. The presentation was short and to the point.

They left the meeting feeling: “This is a company that talks about transformation in the same way we do.”

But it was still very early in the process. The art of pitching is often about building knowledge and a solution as you go.

Propose something definitive too early in the process and you risk missing crucial information. Arrive at the answer too late and you may have missed an important chance to connect with the client and build momentum internally.

Publicis Groupe had been invited to pitch alongside the two incumbents, WPP and Omnicom.

The WPP AUNZ side also felt positive about the first meeting. The Campbell Arnott’s team was open about what was needed and asked questions, as the WPP AUNZ team tried to tease out underlying needs of the pitch.

The pitch document itself was detailed, with some of it looking like it was written in the US. However, it was clear that the Australian team was making the decisions, not someone on the other side of the world. They would be able to make their own call.

And at the end of the first meeting, the half dozen members of the WPP AUNZ team, including a media strategist and creative director, felt they had a good grasp on what Campbell Arnott’s needed.

The requirements were broad, and the pitch covered multiple geographies, so other specialists were brought in including public relations.

The Publicis team came in cold, without the inside relationships of the other two, both of whom had been working with Campbell Arnott’s for years.

But Matt Cooney, chief growth officer at Publicis Communications, felt an early connection.

“A lot of the conundrums that Campbell Arnott’s were wrestling with were challenges we’d been through as a business,” he says.

“And a lot of the issues they faced in their industry were things that we were overcoming in ours. So the chemistry felt good from the start. There was a matched agenda. We weren’t immediately proposing ‘the answer’ - we’re just not arrogant like that - but there was a sense of both parties working together to get to know each other better and identify the right mutual solution. It helped that the shared commitment to radical change was at the heart of the conversation from the outset. We felt that we could help Campbell Arnott’s based on the changes, and learnings, that we had already been through.”

The Campbell Arnott’s business was attractive and not just because of its size in terms of advertising dollars spent. The real total value of such pitches is rarely reported. However, Campbell Arnott's had an estimated $8.3 million in media spend based on Nielsen Ad Intel.

Decisions on budget and creatives are made at George Street, North Strathfield, in Sydney. Typically a food business of this size would need input for decisions from a head office marketing department across the world. That also meant no complicated relationships with other agencies who do work for the parent company.

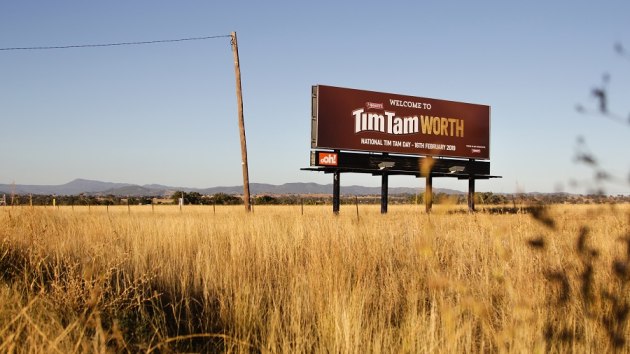

And Campbell Arnott’s has a string of iconic brands with a solid base in the Australian cultural story: such as Tim Tams, Shapes, Mint Slice and Campbell’s Real Stock.

“We wanted the best people because we felt we could reciprocate in a way that many other clients may not be able to offer,” says David McNeil, Chief Marketing Officer at Campbell Arnott’s.

McNeil found, when he joined the business about five years ago, the company was getting excellent work from a range of agencies.

The Kitchen Table

“But it was our opinion that the team here was spending a considerable amount of time coordinating the efforts of all of these various providers,” he says.

“And given we do everything end to end here in North Strathfield, the remit of an average member of my team extends from everything from brand management to innovation, to activation, to administration, you name it. We don't have a Singapore, or London, or New York office to rely upon. So the great team here in Australia and New Zealand are doing just about everything.”

And with a range of providers came different contracts. That meant the solution to any problem was constrained by written arrangements with each supplier. Conflicts arose and that was frustrating and inefficient.

So Campbell Arnott’s devised a more integrated and slimmer agency roster. The Kitchen Table was born.

“We were all members of a bespoke agency called The Kitchen Table,” says McNeil. “It was important that it wasn't Clemenger, it wasn't Wavemaker, and it wasn't Campbell Arnott’s.”

A place where people could sit around, like a kitchen table at home, and be free to offer opinions, to have conversations, to float ideas, to help solve problems, and not have siloed ways of operating.

“We also wanted it to be The Kitchen Table, as opposed to the Dining Table or other metaphors, because we wanted it to be a fun, risk taking culture and pioneer new and different ways of marketing,”says McNeil. “And we felt that by creating a model and giving it a name which embodied those values, it would signal what we were looking for.”

Campbell Arnott’s role was still one of coordination but refined and improved.

“That was the catalyst for us to then go out to market -- a passion for having the best form of integrated model we could possibly get our hands on.”

Linda Abbott, head of integrated communications for Campbell Arnott’s, led a review of The Kitchen Table model. This found that a central P/L and a leader with authority to move resources around were core functions the team needed.

“We took the brief that Linda had put together and we matched that up against individual agencies,” says McNeil. “We quickly concluded that it was going to need to be at the holding company level to find a potential match between that ideal brief and setup and what was available in the market.”

The Pitch

And so the big pitch was born. It started in late 2017 and went into 2018.

The Campbell Arnott’s marketing leadership team led by Linda Abbott wanted a holding company with a fresh approach and a vision of what a fully integrated model would look like.

The process started with McNeil sitting down with each holding company, describing the desire to bring all elements of the agency model under one roof.

He researched each holding company’s website and waved their stated capabilities back at them, challenging them to prove their worth.

He said: “This is what is out in the marketplace and you're purporting to offer this as a model. What we'd like you to do is to come tell us a bit more about that model, a bit more about why you believe you could help us to achieve the vision that I just described, and what's the difference between your model and others out there. What evidence or proof points have you got to share with us?”

The briefing documents were succinct and didn’t run to length. Some briefing papers get very technical and run to the size of old telephone books.

“We described our portfolio and the challenge of feeding the many mouths of our portfolio efficiently and effectively,” says McNeil.

“We asked them to respond with a portfolio solution utilising their integrated model as a case study.

“We chose not to get too much into the conventional credentials and reels and rates and discounts and all that stuff. Some of that diligence came much further down in the process but what we were interested in was understanding their vision and traction on their ‘one agency’ model, their approach to how they would solve something like a portfolio strategy for us, who their people were that they were going to put forward and become an extension of, in essence, my team.”

The session with senior leaders from holding companies was open. They were encouraged to ask as many questions as they wanted for clarification and understanding.

Then the holding companies had a week and to come back to Campbell Arnott’s.

Michael Rebelo, CEO, Publicis Groupe, Australia/NZ, remembers telling McNeill: “Two years ago I wouldn’t have been able to, hand on heart ,answer your brief and provide the agency model you want. Today I can.”

Rebelo walked out feeling confident Publicis could win the pitch and then deliver it in reality. He says: “When you feel that at the briefing you know you have a good chance.”

Agencies throw a lot of resources and effort at pitches. It’s a cliche but the process is almost a love-hate relationship. Many dread the long days and nights but get off on the rush working to a deadline, creating something with sweat and nervous energy.

Cold Pizza

The process, generally for the industry, is on the masochistic side, getting off on the fact that it's got to be done at all hours.

However, the process is becoming increasingly complex. There are more stakeholders, including a procurement department which wants to be involved in everything, in detail. Then there’s a chief information officer as well as the chief marketing officer. And deep technical questions about data.

Matt Cooney at Publicis Communications thinks the pitch process can still bring out the best in the industry but that new approaches are needed.

“Historically, the ticking clock of the deadline would drive the key triumvirate of brand strategist, creative director and business lead to interpret and generate solutions at speed and intensity,” he says.

“Focusing on a core team of three traditional disciplines running a pitch is increasingly outdated because you're going to need experts across a much wider range of skill sets and experiences. They have to work hand in hand across creativity, intelligence and technology.”

Public relations, shopper and e-commerce solutions, data platforms, dynamic content, tech stack optimisation, business transformation, social media and influencer expertise also come into play.

“If you’re not focused and/or don’t have a broad frame of reference, an agency can get overwhelmed in a pitch just by the sheer weight of client information in a way that simply wasn’t the case 20 or even five years ago,” Cooney says.

“Pitches are more complex and sophisticated than they’ve ever been. You need a solid plan, great people and a clear roadmap. Any agency who relies on four people hammering it out night after night over cold pizza is not going to be successful.”

Cooney describes the difference between pitches a decade ago and now is that then it was a four-piece band jamming in a studio and now it’s an entire orchestra performing at a live venue.

“You've got so many more people in the room and in the conversation - at both ends,” he says. “I think the trick now, if you're looking to put a pitch together successfully, is matching a clear sense of direction with an open mind and open door to a wider range of contributions.

“The agencies that pitch best often try to cut through the twin devils of complacency and confusion and be really clear about where things need to head and who is doing what. Give a clear sense of what's expected of everybody, and be more realistic about the timeframe.”

Cooney knew the Campbell Arnott’s pitch had to be highly specific, with the right model, built in the right way. A solution with a precise combination of disciplines and processes.

The unspoken brief

He knew what wouldn’t work, such as telling Campbell Arnott’s: "Hey, here is a panacea, here is the off the shelf silver bullet, for all your business problems."

Cooney: “Building the right model was going to be absolutely key. So that meant we had to get the right people in place and in the room together across our entire range of capabilities: media, data, creative, shopper, PR and production. And right from the outset we knew we had to get everybody around a table and talk about what that solution looked like. To work on it in detail together. Not just a talking shop. Rather than it being led by any one discipline, as often happens with the more traditional creative and media agencies, we look at everything and listen to everyone.”

The biggest problem is knowing what the client needs. This might be different to what they say they want. It’s a matter of digging in for understanding.

With Campbell Arnott's, it was obvious that they'd tried a lot of different ways of working with different agencies, and they wanted something bespoke to them.

“With pitches it's often about picking up on the unspoken brief, because you don't know each other in the first meeting,” says Cooney. “You have to be able to pick up the nuance. What's the subtext? And that's become even more complicated because we've got procurement becoming far more central to pitch briefs.”

This is good in a way, in that the process is more formal and rigorous, with a lot more information. But it can be overwhelming for agencies dealing with the amount of data.

A brief involves constant listening, asking questions, building understanding, finding what’s worked and what hasn’t.

“It's often only further along in the process that the real opportunity for any solution becomes clear,” he says.

“If you close off too quickly, you probably haven't seen the complexity. The danger often is, in the rush and the adrenaline and the timing, the ego takes over and people quickly arrive at a solution - whether that's a structural, strategic, or creative answer. It's a balance between getting the momentum going and keeping up the excitement and energy but not rushing to the solution at such a pace that a client you hardly know hasn’t had a proper chance to give you their point of view about what may or may not be the actual issue.”

Campbell Arnott's gave every opportunity to build a conversation and keep it going. Publicis was able to talk about its experiences and learnings with other clients.

Publicis told Campbell Arnott’s: “These are some of the things we've learned are fundamental in getting this right but what do you think?”

Cooney: “You will hear every agency talking about collaboration but in a pitch process it's absolutely vital. You've got to work on it together. It's one of those classic things where the path to a solution will veer off if you’re not working together well because you don't know each other and you don't have that ongoing relationship. So you've got to find a way of trying to build that rapport, and in this case, build a real tangible solution - the best model, skill mix and process .”

A single model

And the clock keeps ticking. A finite amount of time is available to find a solution. In the beginning, the language is formal, a bit awkward, stilted. “You've got a client and an agency talking about fundamental business, strategic or creative issues, and they've only just learned each other's names,” says Cooney.

A pitch can vary from six weeks to six months. With Campbell Arnott’s, the initial brief was at the start of November, then more interim meetings that month, and a presentation from the holding companies in December. And then in the run up to Christmas, meetings were held across the APAC region in Indonesia and in Malaysia because the deal on the table was a regional one. After the Christmas break, discussions continued in January and February.

The multi geography brief added a dimension. Campbell Arnott’s wanted to see how the holding companies would apply this model across the company’s Southeast Asian businesses.

The Malaysian business is mainly pasta and pasta sauce, Prego and Kimball, a local brand. In Indonesia, biscuits are the big seller. New Zealand is also biscuits. In Australia, it’s roughly 80% biscuits and 20% meals.

McNeil at Campbell Arnott’s: “An important criteria for us was to deliver consistency across all of our markets. And we wanted to see that in action, so we visited each of the markets and heard how they would translate a single model into these multiple geographic points.”

Each of the holding companies pitched in each market.

Then the Campbell Arnott’s team regrouped back to Sydney.

Linda Abbott: “We took some time to review all of the responses across all the different geographies and put together our thoughts and considerations. And that was when we were able to make a decision which would best benefit the region.”

McNeil: “Linda and I had some advisers but we didn't have a strict process. We needed approval from the president of the international division but he operates an empowerment model and had delegated to Linda and I to make a choice. So we certainly spent a lot of time talking about the different proposals that we had received and our thoughts around them. All the proposals were of an exceptional quality.”

Cooney spend a lot of time with his teams encouraging consistency. “Part of the art of pitching is stamina,” he says. “I've seen agencies do really well in three meetings only to lose it in the fourth.”

The pressure is always on. And the deal is never done until the close. “Even when you start to get into detailed negotiations you have stay focused and know nothing is certain.” Cooney says.

But a phone call from Campbell Arnott’s saying Publicis was appointed confirmed that sense that the process was going well.

“You think back and there were moments where we felt we were hitting the right markers, that we'd listened to what was important for them as a client. They were nodding and the conversation was flowing,” he says.

A concept Publicis called The Neighbourhood won in the end.

McNeil: “Right from the get go they got our attention with this model they called The Neighbourhood, unique to us that really was an extension of The Kitchen Table concept. The Neighbourhood was an outdoor version: you live in the same street; you're probably close; there are people you see more often than others; you look out for one another, you see each other on a regular basis; but you have your own independence at times.”

Campbell Arnott’s also warmed to Publicis’ honest and transparent approach, and the group’s global Power of One model, which aims for a more powerful, seamless and connected experience for brands and their consumers -- moving beyond partial collaboration to genuine integration.

The key to the Power of One at Publicis is one P&L, one profit centre, which removes internal land grabs, removes duplication and sets a common commercial agenda.

McNeil: “They were open about where they were struggling, where they had learned some lessons and where they still had some work to do.”

The sense was that Publicis was a partner who would collaborate and not claim to have all the answers but who wouldn’t need any hand-holding. McNeil: “They were much more at the same stage of development, if I could put it that way, in terms of realising vision.”

For it to work, everyone within the Campbell Arnott’s team needed to understand the model and to get behind it.

The same challenge applied to Publicis. Everyone had to think of The Neighbourhood as their first team, not the individual agency they worked for.

Rebelo: “This was a unique pitch, as we had to respond on end-to-end agency models across four countries in Asia Pacific, all being led from Sydney. There wasn’t a requirement for creative solutions which was refreshing. It was about the model, distinct capabilities, the chemistry and shared values and ambition. However, we also wanted to impart that we could bring the magic and the connected model.”

Publicis is seeing a shift in the tender and pitch briefs in the market.

“There is certainly a growing need from clients who want a partner that can help drive new customers into their funnel, keep them longer and purchasing more; not one at the expense of the other,” says Rebelo.

“Given the changing needs of clients, the pitch process and briefs are changing as a result. But what hasn’t changed is the chemistry and cultural fit clients are looking for in their marketing partners. We’re still fundamentally a people business.”

Have something to say on this? Share your views in the comments section below. Or if you have a news story or tip-off, drop us a line at adnews@yaffa.com.au

Sign up to the AdNews newsletter, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter for breaking stories and campaigns throughout the day.