Facebook does not automatically delete graphic and violent videos of children being abused, images and videos of self-harm, racist hate speech towards immigrants and even offers protection to known far-right figures, a damning new investigation into the platform’s moderation has revealed.

This year Facebook released a set of guidelines on what was allowed to be published on the platform. Unlike other media there is very little regulation about what content can be published on Facebook, which leaves the decision to delete content up to an outsourced team of around 20,000 moderators.

An undercover reporter from Channel 4’s Dispatches filmed how moderators were being trained at Facebook’s largest moderation centre in Europe, CPL, which is based in Dublin, Ireland.

The reporter was given on-the-job advice in how to deal with extreme content that had been reported by Facebook users as not meeting its community standards, which runs into the millions each week.

Among the revelations was evidence that moderators allow extreme content to stay on platform because it encourages users to spend more time and, therefore, Facebook to serve more advertising.

Facebook has refuted the notion that turning a blind eye to bad content is in its commercial interests.

"This is not true. Creating a safe environment where people from all over the world can share and connect is core to Facebook’s long-term success. If our services aren’t safe, people won’t share and over time would stop using them. Nor do advertisers want their brands associated with disturbing or problematic content," it has since said in a statement.

A trainer, recorded in the investigation, said: “This extreme content attracts the most people. One person on either extreme can provoke 50 to 100 people. They (Facebook) want as much extreme content as they can get.”

Roger McNamee, an early investor in Facebook and former mentor to CEO Mark Zuckerberg, described this dark content as the ‘crack cocaine of the Facebook product’.

He told Dispatches Facebook’s business model is to “publish the harshest, meanest voices that are going to dominate”.

“The more open you make the platform the more inherently bad content you are getting on it,” he said.

The investigative documentary adds weight to suspicions that Facebook’s business model encourages extreme and shocking content to keep users on the platform for longer so that they can be served more ads.

It also raises doubts about Facebook’s ability to adequately police the platform to what many would regard as acceptable community standards despite doubling its moderator workforce to 20,000 people.

Facebook EMEA VP of public policy Richard Allan, who was interviewed about the findings by Channel 4 news anchor Krishnan Guru-Murthy, said the film highlighted alarming mistakes and “weaknesses” where CPL moderators were not adhering to Facebook’s own community standards and would be re-trained.

Allan also strongly disagrees with the claim that Facebook profits from extreme content.

“There is a minority who are prepared to abuse our systems and other internet platforms to share the most offensive kind of material, but I just don’t agree that that is the experience that most people want and that’s not the experience we are trying to deliver,” Allan said.

“The way in which we make money is that we place advertisements in somebody’s news feed. Just like if you watch commercial television, your experience is interrupted by an ad break. Well on Facebook your news feed is interrupted by an ad break. And that then isn’t associated with any particular kind of content. So shocking content does not make us more money. That’s just a misunderstanding of how the system works.”

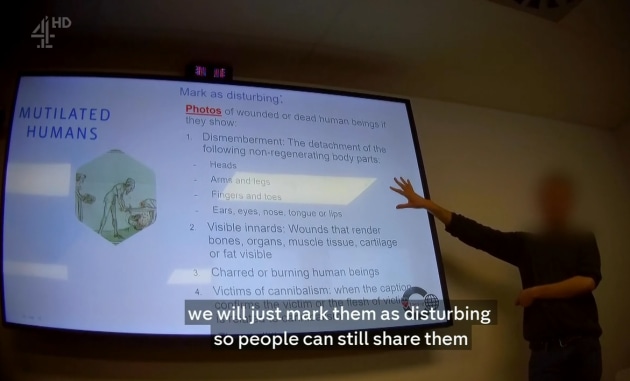

The report detailed how Facebook moderators determine content that is flagged to them as either: ‘ignore’, ‘delete’ or ‘mark as disturbing’.

Only content deemed worth of ‘delete’ gets removed, while ‘mark as disturbing’, means that content should only be viewed by users aged 18 and over and can be escalated to Facebook for internal review.

Facebook does not police who views content that has been labelled ‘mark as disturbing’.

The documentary went through each area of disturbing content and how moderators were being instructed to deal with it.

Since the documentary went to air in the UK, AdNews has received further details from Facebook about what its stated policy on dealing with extreme content on each of these areas.

The statement admits the TV report on Channel 4 has raised important questions about policies and processes, including guidance given during training sessions in Dublin.

"It’s clear that some of what is in the program does not reflect Facebook’s policies or values and falls short of the high standards we expect," the statement read.

"We take these mistakes incredibly seriously and are grateful to the journalists who brought them to our attention."

Child abuse

In dealing with content that relates to child abuse, a CPL employee told the undercover reporter: “Beating, kicking, burning of children or toddlers smoking – we always mark as disturbing, but we never delete or ignore it”.

A disturbing example highlighted in the report was a video of a little boy that had been severely abused by an adult. It stayed up on the platform for six years despite being reported by users.

A trainer said: “A domestic video of someone getting abused ages ago is not getting reported by Facebook to the police.”

Online child abuse campaigner Nicci Astin told Dispatches she referred the video to Facebook to have it removed.

"We got a message back from saying that this video didn't violate their terms and conditions. It was bizarre," Astin explained.

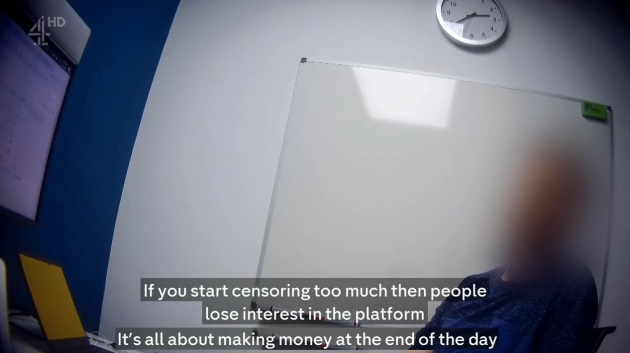

When the undercover reporter asked a CPL moderator why some violent videos are deleted and others are left on the platform with 'mark as disturbing', he responded: "If you start censoring too much then people will lose interest in the platform. It's all about making money at the end of the day."

Even after Dispatches made Facebook aware of this and showed how the video was being used in a training exercise, it stayed up on Facebook at the time Allan was being interviewed.

Allan told Guru-Murthy the video should have been taken down and was “not acceptable”, but conceded that even after it is removed, other users can recirculate it and that Facebook’s automatic filters do not always work.

“Again, somebody has re-shared that video,” he said. “I need to now understand why that’s not been caught by the automatic filters which should be capturing material that we already know about”.

When pressed on why moderators do not automatically remove disturbing cases of child abuse, Allan added:

“So content will be removed if it breaches our standards. I want to be clear that on the site that you went to, the CPL site, you see part of the total system. So those are the frontline reviewers. And indeed, one of their responses is to mark something as disturbing, which means it won’t get seen by people under 18. That’s a very important immediate protection.

“But behind them sits a team of child safety experts. There are actually Facebook full time staff. They work with child safety organisations around the world and they work with law enforcement agencies.

“And material that is problematic and harmful where we think children are at risk, that team reviews – so not the frontline reviewers in the CPL service, but the Facebook full time employees. They will make an assessment of whether the child is at risk. They will make a decision about what to do with the content. Including referring it to law enforcement agencies where that is appropriate.”

The example highlighted was not escalated to Facebook’s internal review team and moderators are not asked to contact law enforcement agencies, which is left to Facebook’s internal reviewers when content is escalated.

Graphic violence

There were plenty more cases of abuse that had not been acted upon by Facebook moderators.

A video of two girls fighting was allowed to run even though one of the girls was clearly being beaten up in a clear act of graphic violence involving minors.

CPL employees looking at a video of two girls fighting commented: “She gets battered. She, you know, at this stage gets kneed in the face. She is helpless, I would say".

The disturbing video, which was viewed more than 1,000 times on Facebook, came to the attention of the victim’s mother the next morning, who said she was distraught because “the whole world is watching”.

Moderators were unclear if such a violent and graphic ordeal should be removed because the video came with a caption condemning the violence and a warning that it was disturbing.

Allan said sometimes people upload videos of graphic violence to condemn bullying and that Facebook wouldn’t automatically remove it unless it was requested by the user involved or a guardian.

“People have, in that case, chosen to upload the video. It’s not Facebook showing it; it’s an individual has said look at this incidence. I want to share this with you and show you something shocking that happened and that can have a very positive effect. People can gather round and say that bullying was awful, let’s all stop the bully,” he explained.

When asked if this reactive system of policing unfairly places the onus on the victim, Allan said: “These decisions are hard and there will be people argue on either side of it. They’re very tough decisions. We’re trying to strike the balance where when people want to highlight a problem, even using shocking material, we don’t stop them from doing that, we don’t cover it up. At the same time protecting individuals who are affected.”

Self-harm

Another contentious area of moderation are videos and graphic images of self-harm.

Facebook automatically removes content where users promote self-harm, but any videos or images that depict acts of self-harm, such as images of slit wrists, is called 'self-hard admission' and left on the social media site without a warning.

The user is then sent a checkpoint, which contains information such as mental health support services.

Aimee Wilson said that she used to post acts of self-harm on Facebook and was encouraged to 'ut a lot more' lf when she saw similar posts by others on the platform.

She said 65% of her self-harm scars are attributed to the impact social media has had on her.

“Someone used to put posts of self-harm. I surrounded myself with people who were self-harmers and it encouraged me to do it more,” she said.

At CPL, a trainee runs through images of self-harm and asks how it should be dealt with.

One trainees responds: "Checkpoint. She's alive I guess. 'I'm fine'". This remark was immediately followed by light laughter in the room.

Allan admitted that Facebook keeps images and videos of self-harm live with warnings that the content is not is suitable for minors.

“Where an individual posts on Facebook ‘I’ve just harmed myself’ or ‘I’m thinking of committing suicide’, our natural instinctive response may be ‘that’s shocking, it could come down’, but actually it’s in the interests of that person for us to allow the content to be up and be viewed by their family and friends so that they can get help,” Allan explained.

“We see that happen every day. That individuals are provided with help by their family and friends because the content stayed up. If we took it down, the family and friends would not know that that individual was at risk.”

Allan was pressed further on whether it was appropriate to leave self-harm content up as minors can easily circumvent age-gates by lying about their age.

“We’re [leaving self-harm content up] in the circumstances you’ve described because somebody is reaching out to their family and friends network through Facebook and we think that allowing them to reach out actually the benefits of that outweigh the harm that are caused by the content staying on the platform,” he responded.

Facebook added that it will send resources to users that post about self-harm for them to receive help.

Hate speech

A CPL moderator working for Facebook revealed that what many ordinary people would define as hate speech won’t be removed if Facebook defines it as political expression.

For example, direct slurs against Muslims are defined by Facebook as hate speech, but if somebody said: “’Muslim immigrants f*** off back to your own country’, then that could be classed as political expression.”

Allan said Facebook faced a difficult task drawing the line between allowing freedom of political expression and legitimate debate, and cracking down on hate speech.

“We’ve not defined it as hate speech. If you are, again, expressing your view about the government’s immigration policy,” Allan said.

“I’m saying we’re trying to define that line so that where people make an expression of their political views, that it is reasonable, even if I disagree with it, you might disagree with it, for somebody to express a view that they don’t want more immigration, they don’t want more immigration from certain parts of the world, they can express that view as a legitimate political view.”

Another example of hate speech that was ignored by moderators in the TV report is a poster of a young white girl having her head dunked into water by her mother with the message: “Daughter’s first crush is a negro boy” – a poster that Allan said has now been removed and failed to meet Facebook’s community standards.

The documentary also suggested that Facebook shielded public figures like far-right activist Tommy Robinson because he had a huge fanbase of 900,000 followers.

The system, known as ‘cross check’, means that CPL moderators can’t delete posts by shielded individuals or organisations. Cross check content receives a second layer of review and can only be dealt with by internal Facebook staff.

This system usually applies to media sites like the BBC or organisations like the Government, but can also apply to individuals with large followings like Tommy Robinson, the former English Defence League founder who is appealing a jail sentence for contempt of court after live-streaming a report of a trial in Leeds.

“We had instances in the past where a very significant page on Facebook with a very significant following could be taken down by the action of somebody in one of the outsource centres pushing a button. And that was problematic,” Allan explained.

“That’s problematic in the sense that what we need to do is make sure that decision is correct. And that’s the cross check point. That we want somebody of Facebook also to look at the decision. If the content is indeed violating, it will go.”

An example where Facebook removed a page was far-right group Britain First after repeated violations.

Is Facebook a publisher?

Last year, YouTube acted swiftly to remove comments by paedophiles under sexualised children’s videos and has claimed down on videos that are brand safe to be funded by advertising.

Facebook has promised to investigate these claims, retrain moderators and update its guidance and training processes.

At the heart of this problem is that Facebook still refuses to accept that it is a publisher and should adhere to the same checks and balances as other publishers, like newspapers and TV news programs, which are legally responsible for the content they distribute, including the extreme views of the people they interview.

Guru-Murthy asked Allan whether Facebook was a publisher and referred to a recent US court case where the social media company argued in court that it was a publisher.

“That’s a legal distinction. There is a legal definition that was argued out in that court case,” he said.

“We’re not a news programme or a newspaper, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have a responsibility. And we accept that responsibility.

“And to your point about regulation, we’re very clear that we do expect there to be more regulation of services like ours and we’re happy to work with governments in order to make sure that that regulation is workable and achieves its objectives.”

If Facebook is unable to adequately moderate footage of hate speech, child abuse and acts of self-harm, as the documentary highlights, regulation may be needed to keep users on the platform safe.

"We have been investigating exactly what happened so we can prevent these issues from happening again," the Facebook statement said.

"For example, we immediately required all trainers in Dublin to do a re-training session — and are preparing to do the same globally. We also reviewed the policy questions and enforcement actions that the reporter raised and fixed the mistakes we found."

Facebook said it provided all this information to the Channel 4 team and included where it disagrees with the analysis.

"This is why we’re doubling the number of people working on our safety and security teams this year to 20,000. This includes over 7,500 content reviewers," Facebook said.

"We’re also investing heavily in new technology to help deal with problematic content on Facebook more effectively."

Further reading: Full transcript of Richard Allan's interview with Krishnan Guru-Murthy. Also check out Facebook's response to the documentary.

Watch the documentary: The documentary can be found at Channel 4's website or here.

Have something to say on this? Share your views in the comments section below. Or if you have a news story or tip-off, drop us a line at adnews@yaffa.com.au

Sign up to the AdNews newsletter, like us on Facebook or follow us on Twitter for breaking stories and campaigns throughout the day.